Critique and Criticism: some people say they are the same thing while others don’t. The Hivemind defines Criticism as

“…the analysis and judgment of the merits and faults of a literary or artistic work.”

and it defines Critique as:

“…a detailed analysis and assessment of something, especially a literary, philosophical, or political theory.”

Not a lot of joy there for my purposes as I find the interchangeability “muddies pools”. To be honest it confuses the heck out of me. The Hivemind has many jumping off points if you want to go down that rabbit hole.

I’ve been puzzling over this for a while and how to apply this to my work. It started when I found a samizdat copies of Terry Barrett’s book “Criticizing Photographs”. This is an excellent book and well worth taking the time to go through (I bought the latest edition; so should you). He uses the term “Photographic Criticism” to refer to a photographer’s body of work or a collection of images while a “Studio Critique” is something that is done in a workshop setting. I’d say that’s reasonable

You have to remember though that not all photographs need to be critiqued. You don’t need to do a deep critique of every picture you take. Sometimes we just shoot for fun and memories; those images don’t need to be dissected like a pithed frog in a biology lab.

However, if you’re serious about your work or you want to be helpful to other people who might ask you for feedback then you do need to understand how to critique an image properly. It is also important to know how to communicate a critique and conversely, how to receive one.

Relying on social media is a no-win scenario. One of downsides of social media is that the only critique you get is an upvote, a like, an emoji or even worse: “Nice capture!.” This doesn’t help you grow as a photographer. It reduces evaluations of images to a popularity contest. Some of us can still remember American Bandstand with Dick Clark. After some series of songs, the alleged teenagers were asked which song they liked. Usually the response was along the lines of “I really liked that first song. It had a beat and you could dance to it.” No mention of the lyrics, no mention of the music, just the beat and danceability. That, alas, is where photography on social media is at as well.

The other pitfall with social media is that you start chasing followers, views, likes, and whatever other metric social media uses to hook you. You start posting photographs that you think others will like and not grow beyond that.

As I said in the beginning of this article there is a difference, to my mind, between an image critique and photographic criticism. Although some elements are (distantly) shared, each has their own methodologies. In this section, I’m going to be drawing on the ideas of photographers and teachers much better and cleverer than myself: Alex Kilbee, Eileen Rafferty, Minor White, Terry Barrett, Judy Hancock, Michael Freeman, and others.

I’m going to start looking at the techniques you can use to critique your own images. Applying these to your own work will provide a starting point for improving your work. Later I’ll look at how to extend those to other photographers’ work. This will help you to deconstruct those images and perhaps improve your own work.

I’m also assuming that you, dear reader, are familiar enough with your craft to understand the technical and non-technical aspects of photography. If you’re not, then I’ve got some links at the end for you to refer to.

Critiquing your own photographs

Being honest about your own work is hard. Incredibly hard. You went out, made images and because of that effort you have become emotionally attached to your creation. I get it. I’m guilty of it and I think every photographer is guilty of it. Self-critique takes an enormous amount of discipline, focus and detachment.

The first step is to cull images. Be honest with yourself. I’ll keep saying that every chance I get.

How you do this is up to you. I’ll go through flagging images in the first pass and continue to refine by setting 1 to 4 stars. Once I get done to the final set, I then start really looking for the final 5-star images.

So now you’ve got some images. Guess what? You’ve done some self-critique! Through this process you’ve identified something in an image that made you reject it or something in an image that made you want to keep it.

Before you start studying your 4-star picks let’s go back and look at the “rejects”. What happens if they’re all rejected? Well, this is when you have to start doing a deep dive. I’ve shot countless rolls of film that have had zero, that’s right, bupkis images that I felt were worth keeping. It’s then that you really have to summon up the courage to go back and really examine these, because this is where the gold is.

What happens if there are no rejections? You’re lying to yourself. Shame on you. No one is that good. No one. Go back and start over and be honest with yourself this time.

Pick some of your rejects and start looking at them. Pick several at random, if possible, from each pass through.

And now, a brief interlude…

What the heck makes a good image? Well, there’s the technical Gang of Four: Focus, Exposure, Sharpness, and Processing. On the artistic side you have this Rest of the Usual Suspects: Subject, Content, Lighting, Composition and Framing. The Go4 and the RoUS I group together as “Craft” or as “The Alleged Rules.”

Overriding all of these though is The High Priest of Context. Context has two parts: Assignment and Vision.

Finally, encompassing all this is something, for lack of a better word, Quux. I’ll talk about “Quux” in a bit.

Focusing (hah!) on just the Go4 and/or the RoUS gives short shrift to an image when critiquing it. HPoC and Quux need to be considered as well or you’re shortchanging the image and yourself.

The HPoC governs the technical and non-technical choices that you make when creating an image. It even governs equipment choice and location. These last two don’t really matter as far as this discussion goes but it makes for an interesting thought experiment.

We’ve all been around long enough to understand what’s part of the Go4 and the RoUS. What may not be clear is how I’m defining the parts of the HPoC.

Paraphrasing Neal Stephenson: “In the beginning was the Assignment” Everybody, even an amateur, shoots to an assignment. You may not think so, but you do. Ask yourself: “Why did I go out to photograph today?” There ya go, there’s your assignment.

Your vision is how you are thinking about and how you are going to approach the assignment. What sort of images are you going to try to create to fulfill the assignment?

This means that the HPoC will drive how you execute the parts of the Go4 and the RoUS. You may end up making creative decisions that may deviate from what the gang of idiots that judge camera club photo competitions think is correct. Remember, the HPoC provides that bit of extra insight when you are doing a critique.

So, what the heck is “Quux” The Jargon File describes it as a metasyntactic variable (look it up). I’m using it as a place holder for a very nebulous idea that is composed of a variety of things. It’s like the umami of the image: the “essence of deliciousness”. It’s the thing that connects the viewer to the image. It’s more than an emotional response, it’s like the “bong” that Lovejoy (a divvy) gets in his chest when in the presence of a true antique. It is the Quuxness of an image that makes an image a truly great image.

You may notice that I’ve danced around the idea of “story.” Well, that’s for a reason. I hate to break it to Rod Stewart and Faces, but not every picture tells a story; not every picture needs to. If you’re into Dada, when they were asked what’s it about, they’d answer: “Dada.” If you’re William Eggleston, he has answered: “That’s the most stupid fucking question I’ve ever heard.” It’s true, look it up. If, however, you are a storyteller by inclination, then the story is important.

We now resume our regular programming…

Where were we? Ah, yes. We’re looking at the rejects. While you were culling, did you note why some images were in and some images were out? What was that? Were the rejects just “meh”, lacking in Quux? Did they not communicate what you thought you were trying to say if you were trying to say anything at all? Did they not match what you saw in your mind’s eye?

The clever boots reading this will notice that I’ve only asked questions relating to the HPoC and the Quuxness of the image. Why is that? Because they really don’t matter all that much. Wait what? You heard that right. Of course, you’re going to try to get the Go4 right but if you don’t it doesn’t matter.

Look at Robert Capa’s D-Day image.

|

| D-Day Landings by Robert Capa |

Exposed correctly? Nope. In focus? Nope. Sharp? Nope. Yet this image uses those three “fails” to produce one of the most potent images of the D-Day landings. It has great Quuxness given its Context.

Here’s another one that serves as an example of Go4 and RoUS “fails”.

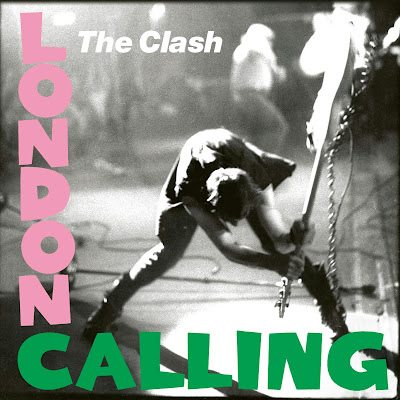

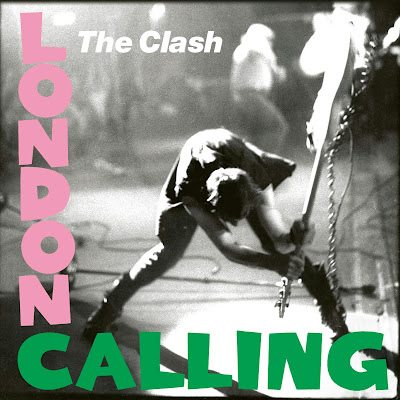

Remember the cover of The Clash’s album “London Calling” shot by Pennie Smith?

|

| The Clash's London Calling Album Cover by Pennie Smith |

This image has an interesting backstory and it’s worth looking up on the HiveMind.

So again, sharp? Nope. In focus? Nope. Exposed correctly? Maybe. Framed? In post yes, when shot no. Composition? In post yes, when shot no. Subject? Again, in post yes, when shot hard to say. Remember she was shooting 35mm film and the image had to be cropped to make a square album cover. The image though, is strong with the Quux.

So go back and look at the rejects to see if any of them have “fails” that contribute to the strength of the image.

Bill Brandt said:

"…photography has no rules. It is not a sport. It is the result which counts, no matter how it is achieved."

It’s not vital to answer the HPoC and Quux questions raised above but they are worth thinking about. Honest introspection is key here. Would it have made a difference if I’d stepped to the left 3 paces, or closer, or farther way? Framed it vertically or maybe if I cropped it? What if I changed the exposure parameters, say underexposed it, changed the lighting or the time of day, changed where I focused, or changed the depth of field? Perhaps it’s just a crap image and you move on. It is through this process of self-examination that one moves forward.

Looking at the images that you feel “made the grade” you go through similar analysis. This is even harder than looking at the culls. A very high degree of self-awareness, brutal honesty and a brutally dispassionate eye is required. This is freaking hard work!

When looking at the “keepers” first ask yourself: “Is this a keeper because I am emotionally invested in the image?” You must remove the self when looking at the image and remove all attachments to the image. Emotional investment is hard to shake. You sat there, in the heat, cold, rain, whatever, waiting for that precise moment that everything came together. You pounded the streets, until at that precise moment there was the image waiting for you. You probably remember the sounds and smells, what your gut felt when you tripped the shutter.

I took a portrait of a pilot who was leaving the company I worked for and took an image of him walking away from me going along the flight line. I can still smell Jet-A. I can still hear a PT-6 starting up. That’s an example of emotional attachment, for both the subject and the photographer. Fortunately, it’s a good image and he has it as his avatar online and has it framed on his desk at home.

Is this image a keeper because it satisfies the Go4 and RoUS, yet you have forgotten the HPoC and the Quux? A technically perfect image can be utterly devoid of life even if it includes the HPoC.

Consider the stock images that litter corporate websites. Here’s one:

|

| A typical stock photo |

Yup, it satisfies the Go4, it satisfies RoUS, it even satisfies the terms of the assignment: “a bland image of diverse employees working together”. Was the vision met? I suppose so. It certainly satisfies the brief. However, a rock has more life than this image. It is just like flavourless Wonder Bread. It is totally devoid of Quux and yet this image and others like it are all over the internet. Dull and dreary without communicating a thing.

You can dive deeper into your own images if you wish. There are many resources on the web, many of them indifferent. I’ve put some links at end of this article. My recommendation is that you take what helps you and discard the rest. But remember these two things:

“…when you look at one of your images how does it make you feel? If it makes you feel like there’s something there, follow that path, follow that passion, follow that creativity.”

-- Greg Carrick

“…it is not the sharpness of the image that people will respond to. They will not, one day in the distant future speak about your stunning histograms.”

-- Dave duChemin

Critiquing Other Photographer’s Work

Well. We seem to have flogged looking at your own images to death. What do you do when you are asked to critique someone’s image? How do you go about it? How do you present the critique? How do you receive a critique if it’s your image that is being looked at. Again, I’m speaking about a single image, not a body of work.

There are three different ways that you may be asked to critique someone’s work: being asked by the photographer in person, being asked online or being in a workshop and having to review an image by someone in the group. Note that I don’t include judging an image for a competition (something I loathe). Judging is a whole other thing, and I don’t want to even go there. Barrett and Minor White to provide some guidance on that subject.

Barrett goes into some depth breaking down the sorts of critiques one can do. I’ll list them here but look to Barrett’s book for a detailed description of each:

- Intentionalist

- Descriptive

- Interpretive

- Judgmental

- Theoretical

I must admit I loathe the word “judgmental.” Growing up in a Calvinist household, the entire concept of judgment leaves me shuddering whenever I hear it. It’s just too final, too negative, no matter how Barrett and others try to sugar coat it. Let’s use the word “feedback” and “evaluative” rather than “judgmental”.

Of all the types of critiques listed, the one that best matches the situation you’ll likely to be in is “Feedback Critique.” The others, while interesting, are not likely to be encountered online or in a photo club setting. Theoretical critiques might happen when, after the meeting, a few too many beers have been consumed!

Before we go any further, we have to remember that photographs have a visual language. Parts are constant across cultures or genres; others are unique to cultures and genres. Like any language, photography has its grammar, its tropes, and its symbols; again these vary because of culture and genre while others are constant.

This all combines to inform a photographer’s vision and voice. This is a whole other area of discussion and is too complex to talk about here, but you do have to be aware of these as you critique others’ images.

You also have to be aware of the skill and experience level of the photographer. You have to adjust your evaluation to reflect this. You can’t evaluate the work of a beginner the same way you evaluate the work of someone who has been making images for decades (although I have seen images by the latter category that sometimes make me wonder if anything has been learned during those decades).

When giving a critique you can’t go all Roman Centurion correcting Brian’s abysmal Latin. It’s just not constructive. Sure, you’ll remember that “Romani ite domum” is correct (usually in a horrifying flashback to your days at school) but I doubt you’ll remember why it is correct.

How do you begin? Start by quick writing. This is a technique where you write about the image for no more than two minutes; even a minute is fine. Don’t worry about grammar, organization, or spelling. Get your reactions down on paper. These are your first reactions to the image and will act as a guide to your feedback and evaluation.

You have to remain objective throughout. You become objective quickly when you realize that the photograph you are looking at is neither good nor bad, but simply, to quote Joe Friday “Just facts”. These facts may add up to be realism, dadaism, expressionism or what ever other “ism” is out there.

Begin (using your quick writing) by describing what you see. Consider the subject matter, how form relates to the subject. Remember to review you evaluations in light of your own assumptions and preexisting ideas.

Describing the purpose (HpoC) of the photograph is difficult if you’re not sitting next to the photographer or have a statement by the photographer to hand. Even a title or a caption is helpful. Absent these you have no idea and you have to rely on educated guesses. Assign purpose by saying: “This image affects me in [some descriptive way] and I believe it serves [some description] purpose because [reasons].” The order doesn’t matter, but you always have to back up your guesses with a well thought out reason.

Now, you can begin to interpret the image. Again, not easy. You have to steer clear of your own biases. Go back to your quick writing. If it contains questions about the image, expand on those. If you have sketched out an interpretation expand on that. Support your interpretation with factual information. If, for example, you feel that the image echoes the work of SomeArtist by SomeTechnique to show SomeStory then say it and support it with facts. If the image takes that SomeArtist’s concept further to define a new way of addressing SomeStory then say it and support it with facts. If however the image merely apes SomeArtist’s image or style or technique and fails then you’re faced with the conundrum of how to (gently) let the photographer know. Facts come to the rescue here. Show why the image has failed and how it could be improved supported by cogent observations of what is in the image. Preferences are not valid observations, they are merely psychological reports on your own state of mind. Thanks to Barrett for that observation.

You have to have the presence of mind however to be open to the idea that the image you are looking at is a whole new style, or a riff of an existing style that has been turned on its head. This usually won’t happen in a photo club or online forum but you have to be aware of a nascent talent’s work landing in your lap. What ever you do, don’t behave like the art critics when they were first exposed to the Impressionists for example. If an image gets your chuddies in that much of a twist sit down, have a cup of tea, and look inward and ask: “What do I fear from this image so much that I am openly hostile towards it?”

Again, I have to reiterate that the image is at the very least technically competent for some value of competent. No image is perfect. Not even the greats would own to their images being perfect. Each image is a step along the road of the “Ongoing moment” (thanks to Geoff Dyer for choosing that title for one of his books).

In the milieu that and will most probably find ourselves, the chance of us being asked to critique a image by SomeFamousPhotographer is vanishingly small.

We’ve described the image and assigned a purpose. We can now do a technical assessment and perhaps provide suggestions to make the image more powerful. Again, using your quick writing and the Craft (Go4 and RoUS) you phrase your suggestions in such away as to be as constructive as possible.

For example, the framing is a bit off so you could say: “Perhaps if the photographer moved a pace to the right it would place the subject to draw the viewer to the subject and away from the tree.” In general you can say: “Perhaps if the the photographer [adjustments element(s) of craft] it would [result]”or: “I wonder is the photographer [adjustments element(s) of craft] what the image would be like.”

Easy Peasy, right? No ruffled feathers, no confrontation and a possibility of opening a dialog about the image.

What happens when the photographer’s vision exceeds their craft? Or their craft exceeds their vision? This can be difficult to deal with and as I have mentioned above, facts come to the rescue and you use these facts to show why the image is lacking and what can be done to improve it. Again, use non-confrontational language. Don’t say: “Nice try, but your exposure sucks and yada-yada-yada.” Just don’t. Instead, say things like “I think I understand your vision, but the [element(s) of Craft] seem a bit off. Maybe you can tell me why you made those choices.” You want to start a dialog so both of you can learn.

The most difficult situation is where there is no Vision and no Craft. The camera has been set on Auto and no thought has been given to communicating anything. In short, a happy snap. You have two choices here.

You can beg off by saying: “I don’t think I’m the right person to critique this image.” This is kicking the can down the road and doesn’t really help anyone – not even yourself as the best way to learn a subject is to try and teach it.

If you are feeling up to it you can possibly try to walk the person through the image pointing out why the image doesn’t work from a HpoC and Quux perspective and how to get around those issues and then elaborate on how Craft (Go4 and RoUS) can support getting to HpoC and Quux. Again, every statement has to be supported by facts and reasons. If you get any push back, just drop it. You may have planted a seed and the photographer may go and do some reading (at best), take a workshop, or jump on the YouChoobies at worst.

Receiving a Critique

What happens when your image is being critiqued? How do you receive that critique? I’m going to assume that the critique you are receiving is done in the same spirit as I’ve describe. If it’s confrontational, aggressive or nasty just say: “Thank you” and move on. Haters are going to hate and it’s best to let them swim in their own poison.

Remember that the critique is of the image, not of you. You may be heavily invested in the image and think that it’s the next “Moonrise Over Hernadez” but that’s immaterial.

Be centered and receptive when receiving the critique. Open your ears. Like Yogi Bera said: “You can see a lot just by listening.” Don’t block out the critique by rushing ahead and creating a list of “Yeah but”. The same applies to a written critique. Read, think, pause, rinse, repeat.

- Go in with an open mind and view this a learning experience.

- Breathe and be mindful.

- Wait before responding.

- Ask for clarification

- Do not accept criticism blindly. Begin a dialog about the image, about your vision, about your craft.

- Don’t disregard positive comments.

- Remember we’re all here to learn.

Useful Resources

Eileen Rafferty

Ms. Rafferty did several excellent videos at the B&H EventSpace on various subjects that are helpful when critiquing an image:

Art Movements in Photography

Designing an Image

Learn the Language of Photography Through Critique

B&H has many excellent videos on their YouTube channel and most of them aren’t product promotions. It’s worth rummaging around in there.

Judy Hancock Holland

Ms Hancock Holland posted this useful video on critiquing your own and others' photographs. She's even published a handy-dandy checklist.

Critiquing Photos: Yours and Others'

Checklist for Evaluating Photos (Yours and Others)

Terry Barrett

Mr. Barrett's book "Criticizing Photographs" is a must read for anyone venturing into the murky world of photographic criticism and critique. You can find it on Amazon and other online booksellers

Aperture

This is one of the grandaddies of photography magazines. The era when Minor White was editor is rich with articles by White, Adams and many others. The article in Volume 2 Number 2 (1953) by Minor White entitled "Criticism" what started all this off for me, way back in the mists of time. I found in the book: "Aperture Magazine Anthology -- The Minor White Years 1952-1976" You can find this book online at the Aperture website and at many other online booksellers.

David duChemin

Mr. duChemin has written many very thoughtful books that actually talk about achieving "Quux". He is insightful, penetrating and a damn fine writer. You see his books on his

website and they are available at the usual online booksellers.

Michael Freeman

Mr. Freeman's books on 35mm photography took me from a tyro aping being a photographer to developing the technical chops to do the job. His series of books. The Photographer's Eye, Mind, Vision, Story (4 books) are well worth reading.

Alex Kilbee

Mr. Kilbee, will you please stop reading my mind! Really. I start writing something and sure enough, three days later he posts something on YouTube that mirrors what I've been mulling over. His YouTube channel is well worth subscribing to. All killer, no filler.